Carl Hart High Price Pdf Diffuser

Pickard:The scientist’s memoir that we will discuss today really begins with his life in the toughest area of Miami, and early on he’s exposed to domestic violence, drugs as a user and a seller, and carries a firearm, all of which will ultimately influence his groundbreaking research. I’m your host, Dr. Maurice Pickard, and you’re listening to Book Club on ReachMD. And with me today is Dr. Carl Hart, Chairman of the Department of Psychology at Columbia University.Thank you, Dr. Hart, for joining us today.Dr.

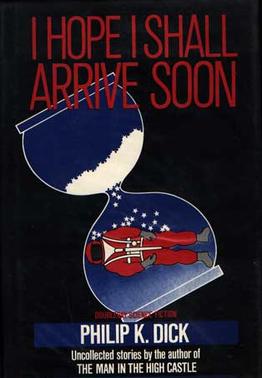

Hart:Thank you for having me. I’m happy to be here.Dr. Pickard:So we’re going to be discussing your book, High Price: A Neuroscientist’s Journey of Self-Discovery That Challenges Everything You Know About Drugs and Society. Hart, why the title?Dr. Hart:The title is society itself, I think that we’re paying a high price in terms of how we view drugs and our approach to drugs.

That price is being paid in multiple domains, whether we think about the people who are using drugs or we think about the US taxpayers, we think about—the book talks a lot about racial discrimination—we talk about the mis-education, so it’s a high price for the society to pay.Dr. Pickard:I know you had written some academic books about the same subject, but I think, in reading your book, you felt that a different message and a different audience was necessary.

So, what prompted you to write this book, which is a combination both of your journey, your life journey, and how you got into the research you did? What was the impetus at that time for you to write this?Dr. Hart:Well, one of the things that happens in American society is that we often times have hysteria surrounding drugs. We have drug crises we call them.

At the moment we have the so-called opioid crises. And invariably, these crises are not informed with real evidence, and society spends a lot of money, for example, on police or on treatment, and where like the majority of the people who are using these drugs are not addicted and they don’t need to be in jail, and so we don’t look at what’s really going on.

Or in the case of the opioid crisis today, we’re concerned about overdose deaths, of course, and we should be, but then when we look and we see that the majority of the people who are dying from opioid-related deaths do so because they combine opioids with another sedative like alcohol or benzodiazepines or even the older antihistamines, but the focus is always and only solely on the opioids, whereas that’s not the real problem. So I thought I’d write this book in response to what we had done previously with crack cocaine, what we had done previously with methamphetamine, all the mis- sort of -information related to those drugs and the misappropriation of funds, and I thought this book would help, and I thought I’d write this kind of book so that it would reach a broader audience. And as I see what’s happening with the current opioid situation today, I feel like, actually, I failed.Dr. Pickard:You’re not the only one who feels that way.

Certainly, when I was in trying, I grew up with the whole concept of that if you use a substance, a controlled substance, that if you just used it once, you would become an addict. It would be like if you took a cigarette, you would definitely be smoking a pack the next day. We now know that this isn’t true, and your research shows that it isn’t true.

This is one of the myths that you explore. Why is this such a myth?

What’s the difference between the people who become addicted and the vast, vast majority who use and can tolerate it?Dr. Hart:Okay, you have 2 questions embedded there. You asked one, which is: Why does this myth persist in terms of one hit of some drug like heroin or crack—why does the myth persist that you are addicted when, in fact, that’s just so far from the truth? One of the reasons that the myth persists is because most of the people in the society don’t know or have not used those drugs and so, therefore, they are susceptible to believe whatever is said about those drugs. And then we have, for example, movies, documentary films, news reports, all of those reports and media sort of things, they suggest that, “Oh, yeah, this is so salacious,” so they reinforce that myth, and so the society is susceptible to believing it. That’s on the one hand. And then the other part of your question was: What separates those people who actually become addicted versus those who don’t?

The thing that we know—whether we’re talking about heroin, alcohol, marijuana, tobacco, it doesn’t matter—what we know is the vast majority of people who use any of those drugs do not become addicted. We’ve known that for decades. We know that for a fact. If that’s the case, then it tells you that addiction is probably not related to the drug itself. There are other factors. And, in fact, what we know too is that a large percentage of the people who are addicted, they also have co-occurring psychiatric illnesses; they have co-occurring other types of illnesses. We know that they have limited opportunities or employment, limited skills.

All of these things tell you that’s where we should look for the sort of factors that separate those people who are addicted versus those who are not. But often times we don’t do that. Instead, we look at the drug and we say heroin is so addictive and we focus on heroin, which is a mistake.Dr.

Carl Hart High Price Pdf Diffuser 2017

Pickard:And you also, in your life in particular, had significant mentors, and that, I think, really was a takeaway that I, when I read your book, how significant, how a casual acquaintance who becomes a mentor can really change your life. And certainly in your case you do mention the mentors that you knew.

I know you had 5 sisters and you had a grandmother, and they were certainly mentors to you, but there were some others as well. Could you comment on the need for mentoring?Dr. Hart:Mentoring, of course, is an important aspect in any of our lives. I mean, often times in the United States we like to say like “pull yourself up by your bootstrap,” by none of us make it without others, and so my story just shows that, that I had a number of people in my life from the early on—early on my family members, coaches or teachers, and then subsequently, professors, researchers, scientists and other people who were there to help with my scaffolding to this point, and people continue to help me.

And so I think it’s illustrative of when we think about how do we best help people succeed, we want to make sure that they have appropriate mentoring, mentoring in their area of specific training like science; and also, social mentoring and other types of mentoring is important too. The thing that’s really important is that we don’t just have 1 mentor, we have multiple mentors. If you don’t have multiple mentors, it decreases the likelihood that you will succeed.Dr. Pickard:If you’re just tuning in, you’re listening to Book Club on ReachMD, and I’m your host, Dr. Maurice Pickard, and joining me today is Dr. Hart has written a very thought-provoking book, the High Price: A Neuroscientist’s Journey of Self-Discovery That Challenges Everything You Know About Drugs and Society.One of the other things that was a takeaway for me, and I hope people will pick this book up and read it—it was very thought-provoking and really expanded my knowledge—was that there was also the opportunity for what you call alternative reinforcement.

You use the rats experiment, which in my medical school career was very common to have a rat press a particular button and take a drug and it would take the drug over and over again and reinforce its success or the feeling it had until it ultimately died. This was something that we really kind of relied on when we took this bit of information and tried to superimpose it on human experimentation, but you have a different take on this. Could you explain that?Dr. So, when I was an undergrad, one of the things that we were taught was that drugs like cocaine or even methamphetamine and heroin were so addictive that if you, for example, connected an animal, whether it’s a nonhuman primate or a rat, up into an intravenous sort of catheter such that when they press a lever they receive intravenous injection of these drugs, and if you gave the animal an opportunity to self-administer these drugs intravenously, they would do so until they died, and that was evident that these drugs were so addictive. We all believed it, and this was dramatic. But they forgot to tell us that the only thing that that animal had access to in the cage was the lever leading to the intravenous injection.

So, if you only had that lever in your cage, of course you’re going to press that lever, and you will press that lever until you die. But then Bruce Alexander and some other researchers—Bruce Alexander was then working at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver—he showed that when you provide rats with alternatives, other options in their cage other than the drug itself, along with the drug itself I should say, things like sexually receptive mates, toys, sweet treats, the animals did not take those drugs to death. In fact, they engaged in these other activities more often than drug-taking. So that led us to do study with humans where we provided people who, for example, were addicted to crack cocaine and we brought them into the lab and we provided them with a choice between a hit of crack cocaine and something as small as $5, and what you see is that when they have a choice, they take drug on about half of the occasions and $5 on the another half of the occasions.

But when you increase that amount to something like $20, they almost never take drug; they take the money instead. It tells you the power of providing alternative reinforcements, alternative or attractive reward, they will compete with drug-taking behavior. I mean, think about it.

We, you, me, other folks, when we go We all have jobs, but we also have available drugs, even alcohol. We don’t take alcohol when we go to work because we have other things to do, but if we had nothing else to do, we might take alcohol until it’s so disruptive that we do nothing else but take alcohol.Dr. Pickard:You know, this is science that you’re talking about, and policy should follow science. We have seen, forgetting the whole subject of drugs for the moment, how this often doesn’t happen. We’ve seen it in AIDS and we’ve seen it in Ebola where policy is set up almost disregarding what’s happening in the scientific community.

What can we do And you may disagree. What can we do to make science be the leader and policy follow science?Dr.

Hart:Wow, that’s a great question. So, when we think about how do we make policy be more informed by science or empirical information, one of the things that must happen then is that scientists have to become better at translating their research findings for the general public and policymaker.

Often times, science, the results and the research is pretty complicated and the findings can sometimes be very nuanced, and policymakers sometimes don’t have time for the nuance, and so that makes it difficult on the one hand. Carl Hart, who grew up in one of Miami’s toughest neighborhoods, escaped a life of crime and drugs and avoided becoming one of the crack addicts he now helps treat as the Chair of the Department of Psychology at Columbia University. His landmark, controversial research is redefining our understanding of addiction and demonstrates how personal experience and scientific study can inform and validate each other for a deeper understanding of human behavior and addiction.Host Dr. Maurice Pickard talks with Dr.

Hart, author of the book High Price, about the relationship between drugs and pleasure, choice, and motivation, both in the brain and in society. They explore how his research sheds new light on common ideas about race, poverty, and drugs, and explain why current policies are failing.

Pickard:The scientist’s memoir that we will discuss today really begins with his life in the toughest area of Miami, and early on he’s exposed to domestic violence, drugs as a user and a seller, and carries a firearm, all of which will ultimately influence his groundbreaking research. I’m your host, Dr. Maurice Pickard, and you’re listening to Book Club on ReachMD.

And with me today is Dr. Carl Hart, Chairman of the Department of Psychology at Columbia University.Thank you, Dr. Hart, for joining us today.Dr.

Hart:Thank you for having me. I’m happy to be here.Dr. Pickard:So we’re going to be discussing your book, High Price: A Neuroscientist’s Journey of Self-Discovery That Challenges Everything You Know About Drugs and Society.

Hart, why the title?Dr. Hart:The title is society itself, I think that we’re paying a high price in terms of how we view drugs and our approach to drugs. That price is being paid in multiple domains, whether we think about the people who are using drugs or we think about the US taxpayers, we think about—the book talks a lot about racial discrimination—we talk about the mis-education, so it’s a high price for the society to pay.Dr. Pickard:I know you had written some academic books about the same subject, but I think, in reading your book, you felt that a different message and a different audience was necessary.

So, what prompted you to write this book, which is a combination both of your journey, your life journey, and how you got into the research you did? What was the impetus at that time for you to write this?Dr. Hart:Well, one of the things that happens in American society is that we often times have hysteria surrounding drugs. We have drug crises we call them. At the moment we have the so-called opioid crises.

And invariably, these crises are not informed with real evidence, and society spends a lot of money, for example, on police or on treatment, and where like the majority of the people who are using these drugs are not addicted and they don’t need to be in jail, and so we don’t look at what’s really going on. Or in the case of the opioid crisis today, we’re concerned about overdose deaths, of course, and we should be, but then when we look and we see that the majority of the people who are dying from opioid-related deaths do so because they combine opioids with another sedative like alcohol or benzodiazepines or even the older antihistamines, but the focus is always and only solely on the opioids, whereas that’s not the real problem.

So I thought I’d write this book in response to what we had done previously with crack cocaine, what we had done previously with methamphetamine, all the mis- sort of -information related to those drugs and the misappropriation of funds, and I thought this book would help, and I thought I’d write this kind of book so that it would reach a broader audience. And as I see what’s happening with the current opioid situation today, I feel like, actually, I failed.Dr.

Pickard:You’re not the only one who feels that way. Certainly, when I was in trying, I grew up with the whole concept of that if you use a substance, a controlled substance, that if you just used it once, you would become an addict.

It would be like if you took a cigarette, you would definitely be smoking a pack the next day. We now know that this isn’t true, and your research shows that it isn’t true. This is one of the myths that you explore. Why is this such a myth?

What’s the difference between the people who become addicted and the vast, vast majority who use and can tolerate it?Dr. Hart:Okay, you have 2 questions embedded there. You asked one, which is: Why does this myth persist in terms of one hit of some drug like heroin or crack—why does the myth persist that you are addicted when, in fact, that’s just so far from the truth?

One of the reasons that the myth persists is because most of the people in the society don’t know or have not used those drugs and so, therefore, they are susceptible to believe whatever is said about those drugs. And then we have, for example, movies, documentary films, news reports, all of those reports and media sort of things, they suggest that, “Oh, yeah, this is so salacious,” so they reinforce that myth, and so the society is susceptible to believing it. That’s on the one hand. And then the other part of your question was: What separates those people who actually become addicted versus those who don’t? The thing that we know—whether we’re talking about heroin, alcohol, marijuana, tobacco, it doesn’t matter—what we know is the vast majority of people who use any of those drugs do not become addicted. We’ve known that for decades. We know that for a fact. If that’s the case, then it tells you that addiction is probably not related to the drug itself.

There are other factors. And, in fact, what we know too is that a large percentage of the people who are addicted, they also have co-occurring psychiatric illnesses; they have co-occurring other types of illnesses.

We know that they have limited opportunities or employment, limited skills. All of these things tell you that’s where we should look for the sort of factors that separate those people who are addicted versus those who are not. But often times we don’t do that. Instead, we look at the drug and we say heroin is so addictive and we focus on heroin, which is a mistake.Dr. Pickard:And you also, in your life in particular, had significant mentors, and that, I think, really was a takeaway that I, when I read your book, how significant, how a casual acquaintance who becomes a mentor can really change your life. And certainly in your case you do mention the mentors that you knew.

I know you had 5 sisters and you had a grandmother, and they were certainly mentors to you, but there were some others as well. Could you comment on the need for mentoring?Dr. Hart:Mentoring, of course, is an important aspect in any of our lives. I mean, often times in the United States we like to say like “pull yourself up by your bootstrap,” by none of us make it without others, and so my story just shows that, that I had a number of people in my life from the early on—early on my family members, coaches or teachers, and then subsequently, professors, researchers, scientists and other people who were there to help with my scaffolding to this point, and people continue to help me. And so I think it’s illustrative of when we think about how do we best help people succeed, we want to make sure that they have appropriate mentoring, mentoring in their area of specific training like science; and also, social mentoring and other types of mentoring is important too. The thing that’s really important is that we don’t just have 1 mentor, we have multiple mentors.

If you don’t have multiple mentors, it decreases the likelihood that you will succeed.Dr. Pickard:If you’re just tuning in, you’re listening to Book Club on ReachMD, and I’m your host, Dr. Maurice Pickard, and joining me today is Dr. Hart has written a very thought-provoking book, the High Price: A Neuroscientist’s Journey of Self-Discovery That Challenges Everything You Know About Drugs and Society.One of the other things that was a takeaway for me, and I hope people will pick this book up and read it—it was very thought-provoking and really expanded my knowledge—was that there was also the opportunity for what you call alternative reinforcement. You use the rats experiment, which in my medical school career was very common to have a rat press a particular button and take a drug and it would take the drug over and over again and reinforce its success or the feeling it had until it ultimately died. This was something that we really kind of relied on when we took this bit of information and tried to superimpose it on human experimentation, but you have a different take on this. Could you explain that?Dr.

So, when I was an undergrad, one of the things that we were taught was that drugs like cocaine or even methamphetamine and heroin were so addictive that if you, for example, connected an animal, whether it’s a nonhuman primate or a rat, up into an intravenous sort of catheter such that when they press a lever they receive intravenous injection of these drugs, and if you gave the animal an opportunity to self-administer these drugs intravenously, they would do so until they died, and that was evident that these drugs were so addictive. We all believed it, and this was dramatic. But they forgot to tell us that the only thing that that animal had access to in the cage was the lever leading to the intravenous injection. So, if you only had that lever in your cage, of course you’re going to press that lever, and you will press that lever until you die. But then Bruce Alexander and some other researchers—Bruce Alexander was then working at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver—he showed that when you provide rats with alternatives, other options in their cage other than the drug itself, along with the drug itself I should say, things like sexually receptive mates, toys, sweet treats, the animals did not take those drugs to death. In fact, they engaged in these other activities more often than drug-taking. So that led us to do study with humans where we provided people who, for example, were addicted to crack cocaine and we brought them into the lab and we provided them with a choice between a hit of crack cocaine and something as small as $5, and what you see is that when they have a choice, they take drug on about half of the occasions and $5 on the another half of the occasions. But when you increase that amount to something like $20, they almost never take drug; they take the money instead.

It tells you the power of providing alternative reinforcements, alternative or attractive reward, they will compete with drug-taking behavior. I mean, think about it.

We, you, me, other folks, when we go We all have jobs, but we also have available drugs, even alcohol. We don’t take alcohol when we go to work because we have other things to do, but if we had nothing else to do, we might take alcohol until it’s so disruptive that we do nothing else but take alcohol.Dr.

Pickard:You know, this is science that you’re talking about, and policy should follow science. We have seen, forgetting the whole subject of drugs for the moment, how this often doesn’t happen. We’ve seen it in AIDS and we’ve seen it in Ebola where policy is set up almost disregarding what’s happening in the scientific community. What can we do And you may disagree. What can we do to make science be the leader and policy follow science?Dr. Hart:Wow, that’s a great question. So, when we think about how do we make policy be more informed by science or empirical information, one of the things that must happen then is that scientists have to become better at translating their research findings for the general public and policymaker.

Often times, science, the results and the research is pretty complicated and the findings can sometimes be very nuanced, and policymakers sometimes don’t have time for the nuance, and so that makes it difficult on the one hand. Carl Hart, who grew up in one of Miami’s toughest neighborhoods, escaped a life of crime and drugs and avoided becoming one of the crack addicts he now helps treat as the Chair of the Department of Psychology at Columbia University. His landmark, controversial research is redefining our understanding of addiction and demonstrates how personal experience and scientific study can inform and validate each other for a deeper understanding of human behavior and addiction.Host Dr. Maurice Pickard talks with Dr.

Hart, author of the book High Price, about the relationship between drugs and pleasure, choice, and motivation, both in the brain and in society. They explore how his research sheds new light on common ideas about race, poverty, and drugs, and explain why current policies are failing.